An Introduction to Studying the Qurʾānic Sciences

Fully encompassing the questions of a given science and comprehending its rulings is always necessarily contingent upon mastering its introductory aspects, which are the keys to unlocking the doors to its mysteries and which remove the obstacles that veil and conceal it.As such, this study is an attempt to expound upon some of the introductory aspects of the Qurʾānicsciences, paying particular attention to defining the field and outlining its history and canonical sources.

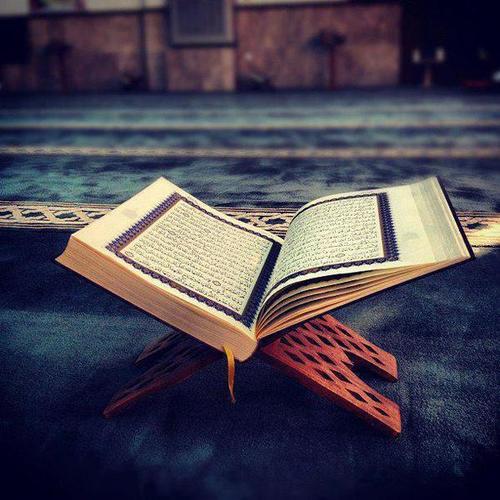

It is the speech of Allah that is revealed to His Prophet Muḥammad, the peace and blessings of Allah be upon him, that is miraculous in its utterance, that is recited as an act of worship, that was transcribed through multiple chains of transmission, and that is written in the musḥafs beginning with “Surat al-Fātiḥa” (The Opening) up to “Surat al-Nāss” (The People).

The Linguistic Definition of the Qurʾān: Scholars have disagreed about it from a number of angles – whether it contains a hamza or not, whether it is an infinitive or an adjective, and whether it is derived from a root word or not. Different schools and opinions have formed concerning its definition and these three points of contention, reaching nearly ten different opinions.

To summarize:From among the various opinions that have circulated concerning its definition and the great attempts in clarifying this issue[1], the correct opinion concerning the word “al-Qurʾān” is that it is derivative (from a root), whether it is an infinitive or an adjective, and its root is Q-R-A, and among its most important definitions are to recite and to gather. It was then employed in reference to the multiply transmitted speech of Allah, the Almighty and Sublime, that is contained between the two covers of the musḥafuntil it came to signify a proper name that referred exclusively to it. As for the question of whether or not there is a hamza, this issue relates to the linguistic dialects of the Arabs, and God knows best; for some of them affirm the hamzain the original word, while others drop it for greater ease. The hamzain the word the Noble “Qurʾān” is recorded as dropped, as is the case in the language of the Hijāz, and al-Shafiʿī, may Allah have mercy upon him, is Makkan, as is well known . . . And God knows best as to the truth and what is most accurate.

The Theological and Sharīʿa Definition of the Noble Qurʾān: the scholars of Islam have typically studied the Qurʾān from two angles, the first being from the theological perspective as the Word of Allah, the Most Exalted, that originates from Him. The Ahl al-Sunna wal Jamāʿā (the mainstream of Sunni orthodoxy) have described as “the Speech of Allah, the Most Exalted, in its true Reality, and not in a mere interpreted or figurative sense.” This is in contrast to the view of the Muʿtazilī school, given that it is uncreated, and it is in contrast to the view of the Ashʿarīs, given that it is not merely personal speech, but it is a quality of an Essence and an action that is sacred; in this case the sound, vocalization, and its singing belongs to the reciter, while the speech itself belongs to the Originator, Most Glorified and Exalted is He. It is thus ascribed to Allah, the Most Glorified and Exalted, in terms of its words and meaning . . .

As for the second angle, they have viewed it as the source of Islamic Law and as the depository of the most sublime speech of the Arabs, and their most refined constructions and disciplines derive their rulings from its wording. For this reason, the legal theorists (usūliyyūn), jurists (fuqahāʾ) and rhetoricians (balāghīyyūn) paid closer attention to the wording aspect of the Qurʾān than to its advanced theological aspect.

Scholarly Disagreement Over Defining the Qurʾān:Some have refrained from defining it, while the majority have done so, and those who refrained from doing so differed among themselves in the reasons for not defining it, while those who attempted to define it also differed in their methodology of how to go about defining it and in their actual definitions as well.

· Some refrained from defining the Qurʾān because it is personal speech, while definitions are for comprehensive categories.

· Others have refrained arguing that the Qurʾān is beyond definition, and it is well distinguished and is not obscure, suggesting there is no need to define it.[2]

· Others have refrained from defining the word itself, preferring to provide a sensory or intellectual definition; “Its true definitionis known through picturing it in the mind or witnessing it through the senses, as if you are pointing to it written in the musḥaf or recited on the tongue, and thus we say: it is what is between these two covers, or we say it is from {Bism Illah al-Raḥman al-Raḥim. Al-ḥamdu lil Allahi Rabb al-ʿĀlamīn} until His saying {Min al-jinnati wal nāṣṣ}.”[3]

· Some of those who have defined it have chosen to reject the principles and constraints of logic, arguing that such tools are incapable of defining the Qurʾān, that they only lead to further obfuscation and confusion, or that the Qurʾān is in no need of them.[4]

· As for the others who have defined it, they relied upon in their definitions on the unique qualities and distinguishing elements of the Qurʾān; some have sought to be expansive in their definitions in accordance with its multiple qualities and unique aspects such as its revelation, its writing in the musḥafs, its recording through multiple chains of transmission, its inimitability, its recitation as an act of worship, and its memorization by heart. Some restricted their description to the two features of its revelation to the Prophet, the peace and blessings of Allah be upon him, and its inimitability due to the Qurʾān’s self-actualization through these alone during the age of Prophethood, while others who mentioned other qualities did so in order to define it for those who were not witnesses to the age of Prophethood. Others still have dropped the quality of its miraculous inimitability, arguing that this is a very specific quality that can only be appreciated by the knowledgeable elite who are familiar with the secrets of the Arabic language and its manners and also because this quality does not encompass all the parts of the Qurʾān, for its inimitability, according to what has been narrated, only applies to the length of a Sura or its like.[5]However, others have argued that restricting its definition to the unique quality of its miraculous inimitability is more fitting and concise because “it is an intrinsic quality of the Qurʾān, given that it is the great Sign that confirms the message of our Prophet Muhammad, the peace and blessings of Allah be upon him.”[6]Thus, in clarifying these different positions on the definition of the Qurʾān stemming from its multiple qualities, Ustadh Fahd al-Rūmī[7] states,“The Noble Qurʾān has been characterized by many unique qualities, and perhaps these unique qualities are the reason for the differences in its definition among the scholars; for every definition mentions a unique feature of the Qurʾān that is a defining feature for one scholar and that is overlooked by another. For this reason, we have multiple definitions.” He then provides an analogous example and states, “If we have a tall man wearing a white garment with a red robe, and he is surrounded by men who are shorter in stature and are wearing garments of various colours with white robes, and you were to call him as the tall man, or the one with the white garment, or the one with the red robe, you would have clearly identified him; the individual intended in each description is one, though the descriptions may vary in nature.” The following are some examples of these different definitions that have been provided:

· Abu Ḥāmid al-Ghazālī (d. 505 AH) in al-Mustasfā, 1/101: “The definition of the book is what has been transmitted to us between the two covers of the musḥafin the seven styles of recitation(aḥruf)[8]through multiple chains of transmission.”[9]

· Shaykh Muwaffaq b. Qudāmah (d. 620 AH): “The Book of Allah is[10] His Speech . . . and it is what has been transmitted to us between the two covers of the musḥaf through multiple chains of transmission.”[11]Perhaps he limited himself to these two features because they are the most concise in distinguishing it.

· Al-Shawkānī (d. 620 AH): “As for the conventional definition of the Book, it is the Speech that is sent down to the Messenger that is written in the musḥafs and that has been transmitted to us through multiple chains of transmission.” He also said, “It is the Speech of Allah that is sent down to the Messenger that is recited and verified through multiple chains of transmission.”[12]

· It is the name of this revealed Arabic speech if it begins with the definite article ‘al.’[13]

· The words that are sent down to the Prophet Muhammad, the peace and blessings of Allah be upon him, beginning withSurat al-Fātiḥa till the end of Surat al-Nāss.[14]

· The Speech of Allah, the Most High, that is sent down to Muhammad, the peace and blessings of Allah be upon him, whose recitation is an act of worship.[15]

· It is the inimitable Speech that is sent down upon the Prophet, the peace and blessings of Allah be upon him, that is written in the muṣḥafs, transmitted through multiple chains, and whose recitation is an act of worship.[16]

· The Speech of Allah whose recitation is worship, that is sent down to the Prophet Muhammad, the peace and blessings of Allah be upon him, through the medium of the Archangel Jibrīl, peace be upon him, and that is transmitted to us through multiple chains of transmission and that can be found between the two covers of the musḥaf.[17]

· To summarize: If the aim of a definition (taʿrīf) is comprehension and understanding, then the Qurʾān is known, and as they say, is known that it is in no need of definition. However, if the aim is to distinguish it, then all these meanings have achieved that aim, and God knows best. As such, the most concise definition by which its distinction can be made manifest is the one that is desired, and those seeking a more expanded and detailed understanding should seek it not from the definition but from the various research questions, topics, and rulings discussed in the literature.

Sheikh Mohammad al-Amīn al-Shinqītī states, “Their intention in using these different terms is for the difference in what is understood and not for a change in what is affirmed, for what may be appropriately called the Qurʾān may also be appropriately called the Book (Kitāb)” [Madhkarat Usūl al-Fiqh]. Dr. Muhammad ʿAbd Allah Darāz also states, “This is to clarify the nature of the relation between them, between the meaning that is associated with the term, which is based on what has become popularized through the use[18] of reading (qirāʾa) and in particular recitation, which is the joining of words in proper vocalization,and the use of writing and particular calligraphy, which is the placing of words to together in handwriting; thus if we go back to their original meanings in the language, we see that the two roots K-T-B and Q-R-A connote the general meanings of ‘gathering’ and ‘collecting.’As is hinted in this original meaning, each of the two words is seen to be associated with the meaning of ‘gathering’ (jamʿ), either in the form of the active participle (al-jāmiʿ) or the passive participle (al-majmūʿ). These designations do not simply mean that what is being named is collecting the Suras and verses (āyāt)or is the collection of these Suras and verses, be they in the form of texts that are written on the pages of the hearts, inscriptions inscribed on manuscripts or tablets, or recitations recited on the tongues. Rather, the meaning here is something more precise than all of this, and it is that this Speech has gathered or collected the arts of all meanings and realities, and in it have been gathered the records of all wisdoms and rulings. Thus, if you say al-Kitāb or the Qurʾān, it is as if you are saying, ‘The Speech that is the collection of all the sciences’ or ‘the sciences that are collected in the Book.’ Thus has Allah, the Most Exalted, described it, calling it a {Clarification of all things} [al-Naḥl: 89]. This is also how the Prophet, may the peace and blessings of Allah be upon him, has described it when he said, ‘In it is the news of what came before you, the foretelling of what will come after you and the ruling for what is between you.’”[19]

The shared usage of the term ‘al-Qurʾān’:the word al-Qurʾān is used to denote a small part of it or much of it, and as some have explained, this is the same term that is used in reference to the entire collection of the Qurʾān.

Of the names of al-Qurʾān al-Karīm: the Qurʾān, being the most popular name;al-Kitāb, which is called thus because it collects a variety of stories, verses/miracles, rulings, and news that arenarrated from a number of angles; al-Nūr(the Light) because it reveals the realities and unveils them with its evident clarity and splendid proof; al-Furqān (the Distinguishing Criterion) because it distinguishes truth from falsehood, belief and disbelief, what is lawful from what is unlawful, and good and evil.

A tenet of belief for the Muslim is that the Qurʾān was sent down from the Guarded Heavenly Tablet (al-Lawḥ al-Maḥfuẓ) to the lower worldly heaven in an undifferentiated form, whereas Muhammad received it in gradual installments, i.e. it was revealed to Muhammad verse by verse, and in sets of five, ten, or more or less.[20]The Most Exalted states, {No, it is indeed a Glorious Qurʾān in preserved (heavenly) tablet}. The preserved tablet refers to a great higher world, which Allah, the Most Exalted, has made among the greatest manifestations pointing to the greatness of His knowledge, wisdom, and of His penetrating power over the Universes. This tablet’s function is to record all that Allah, the Most Exalted, has preordained and decreed, that which was and that which shall come to be.[21]

The wisdom behind its gradual revelation:The wisdom behind this is for many reasons. There is wisdom in it for the sake of the Prophet, so that the revelation may continue to be in dialogue and response to the Messenger, teaching him something new everyday, guiding and mentoring him, strengthening his foothold and reassuring him along the way.[22] The Qurʾān itself is witness to this very fact when it states, {And those who disbelieved said, “If only the Qurʾān were revealed to him in one shot”}, to which Allah responds, {We sent it down in this manner so that We may strengthen your heart thereby, and We have arranged it in the best manner}[al-Furqān: 32]. {A Qurʾān that We have made in portions that you may read it upon the people over time, and We revealed it in successive revelations} [al-Isrāʾ: 106].

There is wisdom in it for the Companions as well, in order that the revelation may remain in conversation with them, mentoring them and altering their habits, and in order that it does not surprise them with its new laws and teachings.[23]Furthermore, there was wisdom in it so that they could come to memorize it in their breasts and transcribe it on patches of cloth, and so that putting its meanings into practice is gradually facilitated for them.[24]The ultimate aim in this is to teach the Ummah and habituating it, guiding it, and assisting it in implementing and abiding by Islamic rulings and what is related to them.[25]

The Qurʾān’s Revelation in the Seven Styles of Recitation:

It is established in the authenticated narrations that the Messenger, may the peace and blessings of Allah be upon him, stated, “The Qurʾān was revealed in seven styles of recitation (aḥruf), so read what of it what is facilitated for you.” And in the narration of Muslim, in theḥadīth of Ubay, may God be pleased with him, the Messenger of Allah, may the peace and blessings of Allah be upon him, said, “My Lord sent for me to recite the Quran in one style of recitation (ḥarf), so I responded by asking him to make it easier for my nation, so He sent for me to recite it in two styles, and I responded by asking him to make it easier for my nation, so He sent for me to recite it in seven styles.”

Abu Yaʿla records in his Musnad that ʿUthman, may Allah be pleased with him, said while standing on the minbar(mosque podium), “I bear witness before Allah, that a manheard the Prophet, may the peace and blessings of Allah be upon him, say, “The Qurʾan was sent down in seven styles of recitation (aḥruf), all of which are a healing and sufficient.” He stood up, and they all stood up till they were too many to count, and they bore witness to this, and he said, “And I bear witness with them.” The meaning of this ḥadīth was conveyed by a number of the Companions, and some of the scholars have stressed its narration through multiple chains of transmission.

Furthermore, the scholars have disagreed in a number of schools over the meaning of this ḥadīth, some of the opinions being subject to debate such that they may be deemed unreliable, with some sharing much in common with others and returning to their views. For our purposes, we choose from their opinions the most important two, and we refer anyone wishing to delve deeper in this topic to the books on the readings of the Qurʾān (qirāʾāt):

The first opinion: what is meant by the seven ‘aḥruf’ is a reference to the dialects of different Arab tribes, and it does not mean that each letter (ḥarf) may be read in seven different ways. This is the opinion of al-Qāsim b. Sallām, among others, and it is authenticated by al-Bayhaqī and also selected by Ibn ʿAṭiyya. Ibn al-Juzrī states, “The majority of scholars agree that it is a reference to different dialects.”

The second opinion: what is meant by the seven ‘aḥruf’ is a reference to seven different words of synonymous meaning such as in aqbil, halumma, taʿala, ʿajjil, and asriʿ, etc.(synonyms of ‘come here’). Ibn ʿAbd al-Barr attributes this opinion to a majority of the scholars, and it ascribed to Ubay b. Kaʿb that he used to recite the statement of the Most Exalted, {Whenever it lights for them, they walk in it (mashaw fīh)} [al-Baqara: 20], as “marched in it” {saʿaw fīh). He states, “This is the meaning of the seven aḥruf that are mentioned in the ḥadith traditions among the majority of jurists and scholars of ḥadīth. He states, “And in the muṣḥāf of ʿUthmān, may Allah be pleased with him, the one in the hands of the people today is considered one suchḥarf.” This is the opinion of Imam al-Ṭabarī as well. The editors among the men of knowledge have also gone on to say that seven multiply transmitted readings (qirāʾāt) that are in circulation among the people today are not the same as the seven aḥruf mentioned in the ḥadīth. Rather, these readings are based on the choices of those Imam reciters (qurrāʾ), as each one of them chose a particular reading from what was passed down to them from the Prophet, may the peace and blessings of Allah be upon him, and he had it recited back to him by another student until he became known for it and it was ascribed to him, and what we’ve just summarized is also supported by what has been recorded among the people knowledge, who have stated, “And whoever thinks that every reading (qirāʾa) of one of those reciters is one of the seven aḥrufthat have been stressed by the Prophet, peace be upon him, is gravely mistaken.” Shaykh al-Islam Ibn Taymiyya states concerning this meaning, “There is no disagreement between the reputable scholars that the seven aḥruf that the Prophet, may the peace and blessings of Allah be upon him, had mentioned the Qurʾān was revealed in are not the same as the seven popular readings of the reciters . . .”

Thus, the seven readings that are recited today do not stem from the seven aḥruf. This is what the majority of Muslims uphold from among the earlier and later generations. Building upon this understanding, the ʿUthmānic muṣḥaf that is between us today, as al-Suyūṭī has mentioned, is composed ofthe scripts of the seven aḥruf only and encompasses what the Prophet, may the peace and blessings of Allah be upon him, recited back to the archangel Jibrīl, peace be upon him, and is inclusive of it.

Furthermore, it is also important to note in this regard that the reading that was recited to the Prophet, may the peace and blessings of Allah be upon him, in his final year is the same reading that is available to the people today. To summarize what the scholars have agreed concerning this question, what is meant by the seven aḥrufis a reference to seven distinct dialects of the Arabs, and ʿUthmān, may God be pleased with him, and his fellow Companions gathered the Qurʾān on one of these seven aḥruf, which is the dialect (ḥarf) of Quraysh, and the ʿUthmānic musḥaf has thus come to encompass the Qurayshī dialect, given that its script also encompasses the six remaining dialects. As for the seven multiply transmitted readings, these are all variant readings of this Qurayshīḥarf, and they are carried in the ʿUthmānic script, which was free of any dotting or diacritics at the time. Hence, the ascription of the seven readings to the seven reciters was based on choice and popularity and a close following of what was recorded and narrated and nothing more.

The Prophet, may the peace and blessings of Allah be upon him, receive the Truth in the month of Ramadan, and in Bukhārī it is narrated that Jibrīl used to meet him every night in Ramadan and teach him the Qurʾān, and the first night was on the seventeenth, the Night of Power (Laylat al-Qadr) nineteen years before the Hijra, which corresponded to the month of July in 610 AD, and the Prophet’s age at that time was forty years.

This date is strengthened by what we find in what the Qurʾān discusses concerning another occasion, that of the meeting of the two armies (iltiqāʾ al-jamʿayn) in the Battle of Badr, which also fell on the seventeenth of Ramadan of the second year of the Hijra. See Surat al-Anfāl, 8:41.

As for the Night of Power, it is the first night in which the Qurʾān was revealed, and the following verses were revealed concerning its importance: {The Night of Power is greater than a thousand months . . .} [al-Qadr: 1-5]. The meaning of this is that Allah sent down the Qurʾān as an undifferentiated whole from the guarded heavenly tablet to the lower heaven.[26]

This is confirmed by what is recorded that the whole Qurʾān was in the {highest horizon} since pre-eternity, at the {lote tree of the farthest end, where the eternal Paradise is located}[Surat al-Najm], and after this Allah sent it down in gradual installments to the Messenger in response to his various events and circumstances, as has already been mentioned.

The revealed divine creeds have all come affirming the same belief that Allah, the Most Exalted, alone is worthy of all worship to the exclusion of all other gods. Thus, all the Messengers called upon their people with the same message, {That you shall worship Allah, for you have no god beside Him} [al-Muʾminūn: 32], except that their religious laws (sharāʾiʿ) differed from one revealed law to the other. As Allah, the Most Exalted states, {For every people we have decreed their rites for them to fulfill} [al-Ḥajj: 67].

Thus, the Sharīʿa of Islam has abrogated all the preceding divine laws and superseded them. Furthermore, Allah’s great wisdom, Glorified is He,entailed that He should decree laws for a specific purpose that were to be later abrogated out of a divine wisdom necessitating this abrogation until the laws of the Sharīʿa were finally settled and Allah finally perfected His religion, as in His saying, {Today, I have perfected for you your religion} [al-Māʾīda: 3].

The scholars specialized in this topic have researched the issue of abrogation as one of the research topics in the study of the Qurʾānic Sciences, and some have devoted exclusive monographs to this issue.

Abrogation (Naskh):it is the repealing of a Sharīʿa ruling through another explicit divine decree, meaning that abrogation cannot be based on rational tools or independent legal reasoning (ijtihād).

The scope of abrogation: it is reserved for legal rulings in the form of commands and prohibitions only, and as for theological beliefs and morals, the bases of worship, and any reports not relating to commands and prohibitions, all of these can never be abrogated.

The Importance of Knowing the Abrogating and the Abrogated:

The scholars place great emphasis on understanding the topic of abrogation, given that it is necessary for knowing the Sharīʿa’s legal rulings, to differentiate between the rulings that were preserved and those that were repealed, and they have thus outlined the criteria by which what is abrogating and what is abrogated may be clearly identified. Among these are the following:

An explicit report from the Prophet, may the peace and blessings of Allah be upon him, or a Companion:an example of this is the Prophetic report, “I used to prohibit you to visit the graves, but verily you shall visit them.”[27]An example from the Companions is the statement of Anas b. Mālik, may Allay be pleased with him, related to the story of the Companions at the well of Maʿūna, “Some Qurʾān was revealed concerning them, which we used to read and which was later abrogated: ‘Give news to our people that we have met Our Lord, and He is pleased with us and we are pleased with Him.’”[28]

Abrogation may also be established through aconsensus(ijmāʿ) of the Ummah and by knowing the date of a later ruling from an earlier one. It is worthy to also note that abrogation cannot be established through independent legal reasoning (ijtihād) and nor by a merely apparent contradiction between the sources, for all such matters and what relates themmay not be considered as cases of abrogation.

There are different types of abrogation:

1. Abrogation of the Qurʾān by the Qurʾān: the example of this is the abrogation of the verse of the Most Exalted, {They ask you concerning wine and gambling. Say, “In them is a great sin and some benefits to the people”} [al-Baqara: 219]. This verse was abrogated by the following verse, {Intoxicants, and games of chance, and altars, and divining arrows are a abominations from the work of Satan, so desist from them} [al-Māʾida: 90]. This type of abrogation is valid by consensus.

2. Abrogation of the Sunna with the Qurʾān:such as the abrogation of facing Bayt al-Maqdis in Jerusalem, which was confirmed by the Sunna, with the verse of the Most Exalted, {So turn your face towards the Sacred Mosque (in Makkah)} [al-Baqara: 144]. Another example is the abrogation of fasting the day ʿAshūrāʾ, which was established in the Sunna, with the command to fast the month of Ramadan in the verse of the Most Exalted, {Whomever of you witnesses the month, shall fast therein} [al-Baqara: 180].

3. Abrogation of the Sunna with the Sunna: an example of this is the abrogation of the permissibility to engage in temporary mutʿa marriages, which used to be initially permissible, and was later prohibited. It is reported on the authority of Iyās b. Salmah, on the authority of his father, who said, “The Messenger of Allah, may the peace and blessings of Allah be upon him, permitted mutʿa marriages in the year of Awṭās but later prohibited them.”[29] Al-Bukhārī has a specific chapter subheading for this issue entitled, “The Messenger of Allah, may Allah bless him and grant him peace, forbade the mu'ta (temporary) marriage later.”

Abrogation comes in the Qurʾan in three modes:

I) Abrogation of both the recitation and the ruling: such as in the ḥadīth of ʿĀʾisha, “Among what was revealed was the prohibiting of ten foster relatives, which were abrogated later on by five foster relatives.” Narrated by Muslim and others.

II) Abrogation of the ruling but not the recitation: such as in the example of the verse of the Most Exalted, {Now, Allah Has lightened your burden, for He knows that there is weakness in you. If there are one hundred of you who are patient, they will defeat two hundred. And if there are one thousand of you, they will defeat two thousand by Allah's leave. Allah is with the patient.} [al-Anfāl: 66].This verse has abrogated the ruling of the previous verse, while the recitation of that verse remains, and it is the following, {O prophet, urge the believers to fight. If there are twenty of you who are patient, they will defeat two hundred. And if there are one hundred of you, they will defeat one thousand from amongst the disbelievers; that is because they are a people who do not comprehend} [al-Anfāl: 65].

III) Abrogation of the recitation but not the ruling: An example of this is the above ḥadīth of ʿĀʾisha, may Allah be pleased with her, “. . , which were abrogated later by five foster relatives.” Specifying the number of foster relatives at five remains established as a ruling without its recitation.

The presence of abrogation in the Sharīʿa has many wisdoms associated with it, among them being attending to the interests of Allah’s servants. Indeed, there is no doubt that the interests of the Islamic call at its early beginnings were far different from those after its formation and establishment, and these circumstances dictated changes to some of the legal rulings in order to tend to those interests. This is clear in some of the rulings related to the Makkan and Madinan stages, the beginning of the Medinan era, and the passing of the Messenger, may the peace and blessings of Allah be upon him.

And among the wisdoms behind abrogation also is the trial of Allah’s legal subjects and testing their obedience, wanting the good for this Umma and wanting to reduce their burdens, for if a lenient ruling was replaced with a more stringent one, then this would increase the reward, and if a more stringent one were replaced by a more lenient one, this would lead to greater ease and facilitation.

Revelation (waḥy): It is the communication from Allah, the Most Exalted, to whomever He has chosen among His servants in an instant and hidden manner.

Revelation in the Language and in Conventional Usage:

‘Revelation’ in the language is to cast in a concealed manner. This is confirmed by Ibn Fāris in his Maqāyīs, and the language scholars have provided several variant definitions, but they all go back to the one original meaning of instructing someone in a concealed manner. Ibn Manẓūr defines it as follows, “Revelation: any signaling, writing, message, inspiration, concealed speech, or any such communication that you cast upon anotheris ‘revealing to such and such a communication.’” Thus, what we obtain from their investigation is that ‘revelation’ is to inform in a concealed manner through a variety of modes, the basic constituent element being the presence of concealment, and other elements such as the speed in the vocabulary of the interested party are not constituent to the definition of ‘revelation,’ just as signaling, writing, and direct inspiration to the heart are all among the modes of revelation and its means of communication.

The word ‘revelation’ is used in the Noble Qurʾān in different contexts, all of which confirm and are related to this comprehensive meaning, and thus one may rely on any of these variant senses as a way of relaying and actualizing its comprehensive meaning.

The modes of revelation through which Allah, the Most Exalted, chose to communicate with His Prophet, may the peace and blessings of Allah be upon him, were several, and among them are the following:

1. The direct speech of Allah from behind a veil: this happens in a wakeful state, as was the case on the night of al-Miʿrāj (the Night Journey), and during sleep, as in theḥadīthof Ibn ʿAbbās that the Prophet, may the peace and blessings of Allah be upon him said, “My Lord came to me in the best form – that is during sleep – and He said, ‘O Muhammad,’and I said, ‘At Your service and obedience!’ He said, ‘What are the Highest (angelic) Assembly disputing about?’ I said, ‘My Lord I do not know . . . ‘”[30]

2. Blow of inspiration: this is what Allah casts in the heart of the recipient of what He wills, the Most Exalted, and it falls under the category of revelation that is mentioned in his statement, the Most Exalted, {And it is not for any human being that Allah should speak to him, except by way of revelation (waḥy), or from behind a barrier, or by sending a Messenger to inspire whom He wills by His leave. He is the Most High, Most Wise} [al-Shūrā: 51]. And the Prophet, may the peace and blessings of Allah be upon him, said, “The Holy Spirit (the archangel Jibrīl)blew inspiration into me (nafatha fī rawʿī) that no soul will die until it has completed its appointed term and received its provision in full, so fear Allah and do not be desperate in seeking provision, and no one of you should be temped to seek provision by means of committing sin if it is slow in coming to him, for that which is with Allah can only be attained by obeying Him.”[31] Al-Manāwī states, may Allah have mercy on him, concerning the word rawʿiya in the ḥadīth, “That is, He cast the revelation in my spirit, my consciousness, my self, my heart, ormy mindwithout hearing or seeing it.”[32]

3. The veridical dream vision: On the authority of ʿĀʾisha, the mother of the believers, may Allah be pleased wit her, “The first revelations that the Messenger, may the peace and blessings of Allah be upon him, used to receive were in the form of the true vision in his sleep, and he did not witness anything in his sleep except that it came to be as surely as the morning daybreak”[33] ʿUbaid b. ʿUmair, one of the great Tābiʿīn (generation of Followers), said, “The dream vision of the Prophets is revelation.” He then read the verse, “I see in my dream that I am sacrificing you.”[34]

4. Through the Archangel Jibrīl, peace be upon him, who used to appear to him in these various forms:

1. In his real form in which Allah has created him: On the authority of Masrūq, he asked ʿĀʾisha, may Allah be pleased with her, about the statement of the Most Exalted, {And he saw him on the clear horizon} [al-Takwīr: 23], and she said, “I was the first of this Ummah to ask the Messenger of Allah, may the peace and blessings of Allah be upon him, about this, to which he said, ‘Verily, it is Jibrīl. I did not see him in the form in which he was created except for these two times – I saw him descending from the heaven, the glory of his creation spanning all that is in the heaven and the earth.’”[35]

2. In theform of a ringing bell: On the authority of ʿĀʾisha, may Allah be pleased with her, al-Ḥārith b. Hishām, may Allah be pleased with him, asked the Prophet, may the peace and blessings of Allah be upon him, “O Messenger of Allah, how does the revelation come to you?” He said, “Sometimes it comes to me like the ringing of a bell, which is the most difficult for me (ashaddahu ʿalay), and then this state passes off after I have grasped what is revealed.”[36] Al-Baghawī, may Allah have mercy on him, states, “Concerning his sayingthat ‘it comes me like the ringing (ṣalṣalah) of a bell,’ the ṣalṣalahis the noise of metal when it is struck.”[37]Al-Mubarkafūrī, may Allah have mercy on him, states, “Ashaddahu ʿalay means that this mode of revelation is the most difficult form to receive and understand what is intended because understanding the speech in the case of the ringing is more difficult than understanding the typical speech of a man, and the benefit in this difficulty is what results from this extra effort in terms of drawing nearer (to Allah)and being elevated in spiritual rank.[38]

3. In the form of a man:He is witnessed in this form by the Companions, as in the highly popular ḥadīth of Jibrīl,where he took on the form of an unknown man before the Prophet, may the peace and blessings of Allah be upon him, and asked him about Islam, Imān (belief), and Iḥsān (righteousness). In other instances, they are not able to see him, as is narrated on the authority of Āʾisha, may Allah be pleased with her, that al-Ḥārith b. Hishām, may Allah be pleased with him, asked the Prophet, may the peace and blessings of Allah be upon him, “O Messenger of Allah, how does revelation come to you?” The Messenger of Allah, may the peace and blessings of Allah be upon him, responded, “ . . . and sometimes the Angel takes on the form of a man and speaks to me, and I am able to comprehend what he says.”[39]

The Prophet,may the peace and blessings of Allah be upon him, used to sometimes experience pain when the revelation descended upon him, and this would manifest in sweat on his forehead and brows on the very cold day, while in other times it was easier to withstand, as when Jibrīl would greet him in the form of a man. The most difficult mode of revelation, however, was when it descended as if it were a ringing bell, as we shall see. The Prophet, may the peace and blessings of Allah be upon him, used to be overcome by states upon the descent of revelation, which his Companions around him also witnessed, heard, and felt, may Allah be pleased with him, and in some cases this was accompanied by intense pain or difficulty. Among these instances are what follows:

1. They used to hear near his face a noise like the humming of bees: On the authority of ʿUmar b. al-Khaṭṭāb, may Allah be pleased with him, “Whenever revelation would descend upon the Prophet, may the peace and blessings of Allah be upon him, a sound like the humming of bees would be heard near his face.”[40] It may be that the humming sound was what was heard around the Prophet, may the peace and blessings of Allah be upon him, while what he in fact experienced was more like the ringing of a bell. Al-Ḥāfiẓ b. Ḥajar, may Allah have mercy on him, states, “The humming of bees does not contradict the ringing of bells because the humming heard by those who are present, as in the ḥadīth of ʿUmar may be ‘heard by him as the humming of a bee’ but as the ringing of a bell by the Prophet himself, may the peace and blessings of Allah be upon him. Thus ʿUmar described it as a humming noise from the perspective of those in attendance, while he, may the peace and blessings of Allah be upon him, described it as the ringing of a bell from the perspective of his station.[41]

2. There would be profuse sweating on his forehead and brow, even on an intensely cold day: ʿĀʾisha, may Allah be pleased with her, is reported to have said, “I saw revelation descend upon him on a very cold day, and by the time it ended, he would be sweating from his forehead.”[42] Al-Ḥāfiẓ b. Ḥajar, may Allah have mercy on him, states, “In her remark that this was a very cold day is a sign that the experience of revelation was intensely stressful and exhausting, as the presence of profuse sweatingon a cold day defies the typical course of events, for he would be undergoing an extreme experience that goes beyond ordinary human sensations.”[43]It is also narrated on the authority of ʿĀʾisha in theḥadīth of her innocence (al-barāʾa min al-ifk) that she said, “It appeared as though he was dripping pearls of sweaton a wintery day from the weightiness of (the revelation) that was descending upon him.”[44]

3. His weight would suddenly increase tremendously, such thathis camel mount is about kneel down: Even Saʿīd b. Thābit, may Allah be pleased with him, feared that his leg may be crushed when his leg was placed under the leg of the Prophet, may the peace and blessings of Allah be upon him. On the authority of ʿĀʾisha, it is reported that she said, “The Messenger, may the peace and blessings of Allah be upon him, would receive revelation while mounted on his she-camel, and she would stretch out her neck (fataḍrib bi jirāniha).”[45]Al-Sindī states, “‘Fataḍrib bi jirāniha’: the exterior of the neck, and when a camle wants to rest it stretches its neck on the ground.”[46]

4. He used to be struck with pain: It is reported on the authority of ʿĀʾisha, in theḥadīth of her innocence (al-barāʾa min al-ifk), said, “And by Allah, the Messenger of Allah, may the peace and blessings of Allah be upon him, had barely sought his place and none of the household had exited yet when Allah, the Almighty and Majestic, had sent down (some revelation) upon his Prophet, may the peace and blessings of Allah be upon him,and he was struck by the state of agonizing pain that normally accompanied the revelation.”[47]

5. His face would change, may the peace and blessings of Allah be upon him, by first ashen and then turning red: On the authority of ʿUbāda b. al-Ṣammāt, he said, “Whenever revelation would descend upon the Prophet, may the peace and blessings of Allah be upon him, he would show signs of distress and his face would ashen (tarabbad).”[48] The meaning of tarabbad is that it would turn pale like the colour of ash.

6. He would, may the peace and blessings of Allah be upon him, lower his head and cover it with a garment:On the authority of ʿUbāda b. al-Ṣammāt, he said, “Whenever the revelation would descend upon the Prophet, may the peace and blessings of Allah be upon him, he would lower his head, and so would the Companions, and when its recitation was complete (ʾtuliya), he would raise his head.”[49]

7. He would, may the peace and blessings of Allah be upon him, move his tongue with speed and intensity to memorize from Jibrīl until Allah ordered him to desist, reassuring him that He would gather the Qurʾan in his breast. On the authority of Ibn ʿAbbās, may Allah be pleased with both of them, concerning the verse of the Most Exalted, {Do not move your tongue with it to make haste}, he said, “The Messenger of Allah, may the peace and blessings of Allah be upon him, used to experience a stressful state with the revelation, and he used to move his lips along with it. Thus, Allah, the Most Exalted, revealed {Do not move your tongue with it to make haste; it is for Us to gather and relate it}.” He explained, “He gathered itin your breast to recite.”{So when we recite it, follow its recital}. He explained, “So listen to it carefully. {Then it is for us to clarify it}. Then it is up to us to ensure that you recite it. Thus, from then on, the Messenger of Allah, may the peace and blessings of Allah be upon him, would listen whenever Jibrīl would come to him until, and when he left, the Prophet, may the peace and blessings of Allah be upon him, would recite it as he had recited it.”[50]

8. He would be heard snoring similar to the sound of a young camel:On the authority of Yaʿla b. Umayya, may Allah be pleased with him, he said, “I had wished to see the Messenger of Allah, may the peace and blessings of Allah be upon him, while revelation was descending upon him, so ʿUmar said, ‘Come. Would you like to see the Prophet, may the peace and blessings of Allah be upon him, while he is receiving revelation from Allah?” I said, “Yes!” So, he lifted the edge of the garment (over the Prophet), and I look at him as he was snoring, and I recall he said, ‘like the snoring of a young camel’”[51]

The word for revelation (waḥy) is mentioned in the Qurʾān with the meaning of inspiration, as in the verse of the Most Exalted, {And we inspired Mūsā’s mother, “Suckle him”} [al-Qaṣaṣ: 7]. It is also mentioned with the meaning of (Satanic) whispering (waswasa), as in {And the devils whisper to (or inspire) their friends to argue with you} [al-Anʿām: 121].

II) Defining the Qurʾānic Sciences (ʿUlūm al-Qurʾan)

1. Its meaning, literally or as a construct:

As a construct, ʿulūm al-Qurʾān has two meanings; the first is a literal sense, in which the construct composed of ‘ulūm (sciences) and Qurʾān is taken to mean the sciences and knowledge that are connected to the Noble Qurʾan, whether they are in the service of the Qurʾan in terms of the relevant questions addressed, their associated rulings, and vocabulary or whether the Qurʾān points to their questions and guides their rulings. Thus, the literal meaning of ʿulūm al-Qurʾān encompasses any science that is in the service of the Qurʾānor that takes from the Qurʾan, such as the fields of exegesis (tafsīr), Qurʾānic recitation and intonation (tajwīd), the science of abrogation (ʿilm al-nāsikh wal mansūkh), Islamic substantive law (fiqh), the study of Islamic monotheism (tawḥīd), knowledge of legal obligations, and the Arabic language, among other fields of knowledge.

2. The Conventional definition:

This second conventional definition relates to a distinct field of knowledge with its own recorded body literature. Thus, ʿUlūm al-Qurʾān refers to a recorded field of knowledge consisting of important comprehensive studies related to the Qurʾan from many different areas of inquiry, each of which may be regarded as a distinct science in its own right, and this definition is the best one available for the Qurʾānic sciences from among the definitions out there that are listed by those specialized in this field.

Thus, these are sciences composed of research studies that focus on the Noble Qurʾān from different perspectives including the study of its revelation, such as identifying the chronology of what came first and what came last; the study of the reasons behind the revelation (asbāb al-nuzūl) of some of its verses, the study of what was revealed before the Hijra vis-à-vis what was revealed after it, which came to be identified as the Makkan and Medinan revelations; the study of its script, compilation, and calligraphy; the study of its miraculous inimitability, its unique style, metaphors, and stories; and the study of its exegesis and the clarification of its terms and meanings. And any of these diverse areas of study has its own body of literature, some of which are abridged and others of which are very expansive and detailed.

Perhaps the secret behind naming it Qurʾānic ‘sciences’ (in the plural) is that it is composed of several different research topics, each of which may constitute its own field of inquiry or ‘science’. Thus, for example, a study on the ‘inimitability of the Qurʾan’ may constitute a topic that is its own field and that has many publications under it. Similarly, a study on the ‘Makkan and Medinan revelations’ of the Qurʾan is also a topic that constitutes as its own field of inquiry, just as is the case with a study on the ‘clear and ambiguous (muḥkam and mutashābih)’ verses of the Qurʾān, and so forth. Accordingly, given that scholars have explored and written about and published many diverse topics or fields of inquiry in the service of the Qurʾān, this body of knowledge has come to be named in the plural as the Sciences (ʿulūm) of the Qurʾān, as opposed to Science (ʿilm) of the Qurʾān.

The topic of study is the Noble Qurʾān itself, which may be researched from the perspective of any of the topics above relating to its verses, chapters, reasons for revelation, or Makkan and Medinan revelations.

1. It provides us with a more comprehensive picture of the Noble Qurʾān from the perspective of its revelation, exegesis, compilation, and writing, and whenever this bigger picture is completed in our minds, we are able to better appreciate the sanctity of the Noble Qurʾān in ourselves, and we are able to increase our knowledge of its ways of guidance, its morals, its rulings and its legal prescriptions.

2. This knowledge also helps us to arm ourselves in better responding to the faulty skepticism of the rejecters, the ignorant, and those with malevolent intentions towards the Noble Qurʾān, and it allows to know the necessary conditions that need to be met by those objecting against an interpretation of the Noble Qurʾān and those objecting to the ḥadīth, in terms of is commands and prohibitions.

3. It helps us to better appreciate the extent of the tremendous efforts that were exerted by the scholars of our past in the service of the Noble Qurʾān, some of them devoting themselves to authoring works of exegesis, while others wrote on abrogation, its inimitability, its variant readings, or other specialized topics in the service of the Qurʾān.

The Companions during the Prophetic age were in no need of specialized works in the Qurʾānic Sciences because they were very familiar with this knowledge, and whatever escaped them, they were able to ask the Prophet, may the peace and blessings of Allah be upon him, directly about. By the second century AH, however, the scholars began to write about various topics, and among them were works of Qurʾānic exegesis; among these early exegetes were Yazīd b. Harūn al-Sulamī (d. 117 AH), Shuʿba b. Ḥajjāj (160 AH), and Wakīʿ b. al-Jarrāḥ (d. 197 AH).

By the third century AH, ʿAlī b. al-Madanī (d. 134 AH), the teacher of Imam al-Bukhārī, had authored a work on the reasons for the revelation (asbāb al-nuzūl) of some of the Noble Qurʾān’s verses, Abu ʿUbaid al-Qāsim b. Sallām (d. 224 AH) had authored a work on abrogation and another on the variant readings of the Qurʾān, and Imām Ibn Qutaiba (d. 276 AH) had authored a work on the obscure or ambiguous aspects of the Qurʾān.

The scholars of the fourth century continued to follow through, with Muḥammad b. Khalaf b. al-Mirzabān (d. 309 AH) authoring his work al-Ḥāwī in the Qurʾānic sciences, the Shaykh of Tafsīr scholars Muhammad b. Jarīr al-Ṭabarī authoring his work Jamiʿ al-Bayān fī Tafsīr al-Qurʾān, and Abu Bakr Muhammad b. al-Qāsīm al-Anbārī (d. 328 AH)authoring another book in the Qurʾānic sciences.

As this literature expanded, Abu Bakr al-Sajastānī (d. 330 AH) authored a work on the difficult vocabulary of the Qurʾān (Gharīb al-Qurʾān), and this was followed by Abu Bakr al-Baqillānī (d. 403 AH), who authored a work on the inimitability of the Qurʾān, ʿAlī b. Ibrāhīm Saʿīd al-Ḥawfī (d. 430 AH), who authored a work on the syntax of the Qurʾān, al-ʿIzz b. ʿAbd al-Salām (d. 660), popularly known as the Sultan of the Scholars (Sulṭān al-ʿUlamāʾ), who authored a work on the figurative language (majāz) of the Qurʾān, and Imam Ibn Qayyim (d. 751 AH), who authored a work entitled Aqsām al-Qurʾān. As can be seen by the diversity of these works, each author has tackled a specific field of the Qurʾānic sciences and one of its many diverse topics.

After all these came Imam Badr al-Dīn al-Zarkashī (d. 794 AH), and he authored a comprehensive work entitled al-Burhān fīʿUlūm al-Qurʾān and consisting of four volumes with tens of research questions related to the Qurʾānic sciences. After him came Imam Jalāl al-Dīn al-Suyūṭī (d. 911 AH), who authored his very popular book al-Itqān fīʿUlūm al-Qurʾān, in which he exhaustively summarized the preexisting scholarly literature in the Qurʾānic sciences, though one must caution against it for some of the weak opinions that it includes.

As for the modern period, the number of scholars and works that have been authored in the Qurʾānic sciences is too many to mention, and some of these that are deserving of mention are Iʿjāz al-Qurʾān, by Muṣṭafa Ṣādiq al-Rifāʿī, which is a good book in its field;Tarjamat Maʿānī al-Qurʾān, by his excellency the great Imam (al-Imam al-Akbar) and Shaykh Muhammad Muṣṭafāal-Marāghī, may Allah have mercy on all of them; Manhaj al-Furqān fīʿUlūm al-Qurʾān, by the late Shaykh Muhammad ʿAlī Salāma; al-Bayān fī Mabāḥith ʿUlūm al-Qurʾān, by his excellency the late Shaykh Abd al-Wahhāb ʿAbd al-Majīd Ghazlān; Mabāḥith fīʿUlūm al-Qurʾān, by his excellency Utaẓ Mannāʿ al-Qaṭṭān, which includes a work by Shaykh Muhammad ʿAlī al-Ṣābūnī entitled al-Tibyān fīʿUlūm al-Qurʾān and another valuable work by Shaykh Muhammad TaqīʿUthmānī, one of the great Pakistanī scholars, which is in Urdū and is entitled ʿUlūm al-Qurʾān.

However, perhaps the most comprehensive of these books, the most distinguished among them, the smoothest in style, the most eloquent in expression, and the best one at refuting any directed attacks by the skeptics, whose traces are diseased hearts in relation to the Noble Qurʾān, is Manāhil al-ʿIrfān fīʿUlūm al-Qurʾān, by his excellency, the Ustaẓ and Shaykh, Muhammad ʿAbd al-ʿAẓīm al-Zarqānī, for this work encompasses tens of research topics related to serving the Noble Qurʾān and its related sciences in a manner that benefits both specialists and beginners.

There are many other works, which are too many to mention, that their author’s have dedicated to the service of the Noble Qurʾān and to elucidating what it contains of noble guidance, high morals, and wise counsels.

The Most Important Sources and References From Old and ModernWorks, the Top of Which are These Three:

1. Fahm al-Qurʾān : The first exegetical work of its kind, written by al-Ḥārith b. Asad al-Muḥāsibī (d. 243).

2. Al-Burhān fīʿUlūm al-Qurʾān : by al-Zarkashī (d. 794 AH).

3. Al-Itqān fīʿUlūm al-Qurʾān : by al-Suyūṭī (d. 911 AH).

List of Most Important Works in the Qurʾānic Sciences

1. Al-Itqān fīʿUlūm al-Qurʾān :ʿAbd al-Raḥmān b. Abu Bakr, Jalāl al-Dīn al-Suyūṭī (d. 911 AH). This work serves as a resource compendium covering much of what has been researched in the Qurʾānic sciences.

2. Aḥkām al-Qurʾān of Abu Bakr b. al-ʿArabī:Qādī Muhammad b. ʿAbd Allah Abu Bakr b. al-ʿArabī (d. 543 AH).

3. Aḥkām al-Qurʾān of al-Jaṣṣāṣ: Abu Bakr al-Jaṣṣāṣ, Aḥmad b. ʿAlī, more commonly known as Abu Bakr al-Rāzī al-Jaṣṣāṣ al-Ḥanafī (d. 370 AH).

4. Aḥkām al-Qurʾān of al-Shāfiʿī: Muḥammad b. Idrīṣ al-Shāfiʿī (d. 204).

5. Aḥkām al-Qurʾān al-Karīm: Abu Jaʿfar Aḥmad b. Muhammad b. Salāma b. ʿAbd al-Malik b. Salma al-Azadī al-Ḥajarī al-Maṣrī, more commonly known as al-Ṭaḥāwī (d. 321).

6. Asbāb Nuzūl al-Qurʾan: Abu al-Ḥasan ʿAlī b. Aḥmad b. Muhammad b. ʿAlī al-Wāḥidī, al-Nīsābūrī al-Shāfiʿī (d. 468).

7. Asrār Tartīb al-Qurʾān: ʿAbd al-Raḥmān b. Abu Bakr, Jalāl al-Dīn al-Suyūṭī (d. 911 AH).

8. Iʿjāz al-Qurʾān: al-Bāqillāni, Abu Bakr Muḥammad al-Bāqillānī (d. 403 AH).

9. Iʿrāb al-Qurʾān: Abu Isḥāq al-Zajjāj, Ibrahīm b. Suray b. Sahl al-Zajjāj (d. 311).

10. Iʿrāb al-Qurʾān of al-Asbahānī: Ismāʿīl b. Muhammad b. al-Faḍl b. ʿAlī al-Qurashī al-Ṭulayḥī al-Taymī al-Asbahānī, Abu al-Qāsim, who is given the sobriquet Qawwām al-Sunna (d. 535).

11. Al-Budūr al-Zāhira fī al-Qirāʾāt al-ʿAshr al-Mutawātira min Ṭarīqay al-Shāṭibiyya wal Durra: ʿAbd al-Fattāḥ b. ʿAbd al-Ghanī b. Muhammad al-Qāḍī (d. 1403 AH).

12. Al-Burhān fīʿUlūm al-Qurʾān: Badr al-Dīn Muhammad b. ʿAbd Allah b. Bahādir al-Zarkashī (d. 794 AH).

13. Tārīkh al-Qurʾān al-Karīm: Muhammad Ṭāhir b. ʿAbd al-Qādir al-Kurdī al-Makkī al-Khaṭṭāṭ (d. 1400 AH).

14. Al-Tibyān fī Aqsām al-Qurʾān: Muhammad b. Abī Bakr b. Ayyūb b. Saʿd Shams al-Dīn Ibn Qayyim al-Jawziyya (d. 751 AH).

15. Al-Tibyān fī Iʿrāb al-Qurʾān: Abu al-BaqāʾʿAbd Allah b. al-Ḥusayn b. ʿAbd Allah al-ʿAkbarī (d. 616 AH).

16. Tafsīr al-Laṭīf al-Mannān fī Khulāṣat Tafsīr al-Aḥkām:ʿAbd al-Raḥmān b. Nāṣir al-Saʿdī (d. 1376 AH).

17. Ḥirz al-Amānī wa Wajh al-Tahānī fī al-Qirāʾāt al-Sabʿ: Ibrāhīm b. Musā b. Muhammad al-Lakhamī al-Ghurnāṭī, who is more commonly known as al-Shāṭibī (d. 790 AH).

18. Dalāʾil al-Iʿjāz: Abu Bakr ʿAbd al-Qāhir b. ʿAbd al-Raḥmān b. Muhammad, who is of Farisī origin and Jurjānī of residence (d. 471 AH).

19. Gharīb al-Qurʾān, also titled Nuzhat al-Qulūb: Muhammad b. ʿAzīz al-Sajastānī, Abu Bakr al-ʿUzayrī (d. 330 AH).

20. Faḍāʾil al-Qurʾān: Abu ʿAbd al-Raḥmān Aḥmad b. Shuʿayb b. ʿAlī b. Baḥr b. Sinān b. Dīnār al-Nisāʾī (d. 303 AH).

21. Fadāʾil al-Qurʾān :Abu al-Fidāʾ Ismāʿīl b. ʿUmar b. Kathīr al-Qurashī al-Baṣrī (and later) al-Dimashqī (d. 774 AH).

22. Faḍāʾil al-Qurʾān wa Tilāwatih: Abu al-Faḍl ʿAbd al-Raḥmān b. Aḥmad b. al-Ḥasan al-Rāzī al-Muqriʾ (d. 454 AH).

23. Al-Muqaddima fī Māʿala Qāriʾ al-Qurʾān an Yaʿlamuh: Ibn al-Juzrī Shams al-Dīn Muhammad b. Muhammad (d. 833 AH).

24. Al-Muqniʿ fī Rasm Maṣāḥif al-Amṣār: ʿUthmān b. Saʿīd b. ʿUthmān b. ʿUmar Abu ʿAmr al-Dānī (d. 444 AH).

25. Lubāb al-Nuqūl fī Asbāb al-Nuzūl:ʿAbd al-Raḥmān b. Abu Bakr, Jalāl al-Dīn al-Suyūṭī (d. 911 AH).

26. Mufḥamāt al-Qurʾān fī Mubhamāt al-Qurʾān:ʿAbd al-Raḥmān b. Abu Bakr, Jalāl al-Dīn al-Suyūṭī (d. 911 AH).

27. Muqaddima fī Uṣūl al-Tafsīr: Ibn Taymiyya, Taqī al-Dīn Abu al-ʿAbbās Aḥmad b. ʿAbd al-Ḥalīm al-Dimashqī (d. 728 AH).

28. Manāhil al-ʿIrfān fīʿUlūm al-Qurʾān: Muhammad ʿAbd al-ʿAẓīm al-Zarqānī (d. 1367 AH).

29. Al-Nāsikh wal Mansūkh: Abu Muhammad ʿAlī b. Aḥmad b. Saʿīd b. Ḥazm al-Andalusī al-Qurṭubī al-Ẓāhirī (d. 456 AH).

30. Al-Nashr fī al-Qirāʾāt al-ʿAshr: Shams al-Dīn Abu al-Khayr b. al-Juzrī, Muhammad b. Muhammad b. Yusuf (d. 833 AH).

31. Nuzhat al-Aʿyun al-Nawaẓir fīʿIlm al-Wujūh wal Naẓāʾir: Ibn al-Jawzī, Jamāl al-Dīn ʿAbd al-Raḥmān b. ʿAlī b. Muhammad al-Jawzī (d. 597 AH).

III) The History of “ʿUlūm al-Qurʾān” and its Appearance as Conventional Term

· The Before Writing

The Messenger, may the peace and blessings of Allah be upon him, and his Companions had greater knowledge of the Qurʾān and its sciences than the scholars of later generations, however their knowledge was not properly recorded into fields of knowledge during that period, and nor was it gathered in written works because they had no use for recording it and setting it in writing. As for the Messenger, may the peace and blessings of Allah be upon him, he used to receive the revelation directly from Allah, and Allah, the Most Exalted, has obligated upon Himself with His Mercy to gather it in his breast, such that its proper recitation may be dictated to his tongue and in order that He may reveal to him of its meanings and mysteries. As the Most Exalted states, {Do not move your tongue with it to make haste; it is for Us to gather and relate it} [al-Qiyāma: 16-19]. The Messenger then propagated what was revealed to him to his Companions, and he recited it to the people at a gradual unhurried pacein order that they may properly internalize it, perfect its memorization, and grasp its secrets. The Messenger then explained to them the Qurʾān through his speech, actions, decisions, and morals, all of which constitute his comprehensive Sunna, in fulfillment of His statement, Most Glorified and Exalted is He, {And We sent down to you the Reminder, such that you may clarify to the people what was revealed to them, and perchance they may reflect} [al-Naḥl: 44]. As for the Companions at that time, they were fully Arab, who enjoyed all the distinguished qualities of the Arabs and their perfected features, which included their sharp memories, astute talents, literary taste, comprehension of different styles, and their ability to weigh what they heard according to the mostprecise of measures, such that they were able to actualize the Qurʾānic sciences and its inimitable quality in their inner dispositions and with the purity of their inner natures in a manner that we today are incapable of imitating, despite the vast mercy that has been afforded us with the vast corpus of written sciences and disciplines available.

Though the Companions, may Allah be pleased with them, had these qualities, they were also illiterate and the means of writing were not facilitated for them. Furthermore, the Messenger forbade them to write anything from him other than the Qurʾān, and he told them at the beginning of revelation in what is narrated in Saḥīḥ Muslim on the authority of Abī Saʿīd al-Khudarī, may Allah be pleased with him, “Do not write down anything from me, and whoever has written something other than the Qurʾān shall erase it. And speak about me, for there is nothing wrong in that, but whoever lies about me purposely, then let him prepare his seat in the Hellfire.” The reason for this was out of fear that the Qurʾānic revelation would be confused with something else or that it would become mixed with what does not belong to it, as long as the revelation descended with the Qurʾān.For these combined reasons, the Qurʾānic sciences were not copied down, as was the case with the noble ḥadīth. The first generation continued along this path under the rule of the first two Caliphs Abu Bakr and ʿUmar. Despite this, the Companions remained paragons for emulation in their spreading of Islam, its teachings, the Qurʾān and its sciences, and the Sunnaand in recording it orally without writing.

· The Introductory Period in the Writing of the Qurʾānic Sciences

Then came the Caliphate of ʿUthmān, may Allah be pleased with him, and the abode of Islam had expanded, with the liberating Arabs mixing with different non-Arabic speaking nations, and it was thus feared that the distinguished qualities of the Arabs would be lost from this mixing and change, till there was fear that the Muslims would disagree over the Qurʾān itself if they did not urgently agree upon a single official musḥaf, leading to much disorder and corruption throughout the land. For this reason, ʿUthmān, may Allah be pleased with him, ordered that the Qurʾān be consolidated into a single musḥaf as the standard and that copies be made of it to be sent out throughout the Muslim lands, while the people were ordered to burn all other versions, relying only on this standard version, as we shall see below.

· The Period of Writing Down the Qurʾānic Sciences as a Genre

Then came the written period, in which many works were authored in the different Qurʾānic sciences, beginning with the field of Qurʾānic exegesis, given that it is the mother of the Qurʾānic sciences, which received constant exposure whenever the Qurʾān was being interpreted. And among the earliest authors in the field of exegesis were Shuʿba b. al-Ḥajjāj, Sufyān b. ʿUyayna, and Wakīʿ b. al-Jarrāḥ, whose works collected the sayings of the Companions and Followers (Tābiʿīn).

These are the scholars of the second century AH, and they were followed by Ibn Jarīr al-Ṭabarī (d. 310 AH), whose work is the one of the most brilliant and greatest works of exegesis because he was the first to contrast different interpretations and seek to weigh them against one another (tarjīḥ), as had been done with syntax and the derivation (of rulings). Scholarly attention to Qurʾānic exegesis has continued till the present day, leaving behind a great collection of literature where in we can find works that are impressive and amusing, and that are condensed, expansive, or intermediate. Of these are also exegetical works based on rational opinion (maʿqūl) versus works relying on collected traditions (manqūl). There are also those consisting of commentaries of the entire Qurʾān, of a juzʾ (one thirtieth), or a single Sura, a verse, or the verses related to legal rulings, among other examples.

As for the other Qurʾānic sciences, among its list of authors are: ʿAlī b. al-Madanī, the Shaykh of al-Bukharī, who wrote on the reasons for revelation, and Abu ʿUbaid al-Qāsim b. Salām, who wrote on the topic of abrogation, and both of these scholars are from the third century AH. And of those who wrote on the difficult vocabulary of the Qurʾān (Gharīb al-Qurʾān), we have Abu Bakr al-Sajastānī from the fourth century AH. As for those writing on the Qurʾān’s syntax, we have ʿAlī b. Saʿīd al-Ḥafawī of the fifth century AH. Among the first to author a work on the vague aspects of the Qurʾān (mubhamāt al-Qurʾān), we have Abu al-Qāsim ʿAbd al-Raḥmān, more commonly known as al-Sabīlī from the sixth century AH. And among the scholars of the seventh century AH, Ibn ʿAbd al-Salām wrote on the figurative speech of the Qurʾān (Majāz al-Qurʾān), while ʿAlam al-Dīn al-Sakhāwī wrote on the variant Qurʾānic readings. In this manner, with these works the scholarly sense of determination and effort developed and spurred new sciences on the Qurʾān.

Thus, scholarly works were authored in all these fields, whether be they concerning the oaths and metaphors of the Qurʾān, the proofs of the Qurʾān, its beautiful figures of speech, its script, and other fine topics that you may wish to explore and that may easily fill entire cabinets with the greatest of the world’s literature. These authors have continued till the present day to add to this literature, and the Qurʾānic sciences continue to develop and thrive, while the times come to pass and the world will surelycome to its end; is this not another miracle of the Qurʾān, clearly illustrating for you the limits to which Muslim scholars have soared in the service of revelation?It also shows you that it is a Book whose wonders have no end, whose knowledge is never exhausted, and whose secrets can never be fully encompassed except by its Author and Revealer!

If you add to these Qurʾānic sciences all of what has been recorded of the noble Prophetic ḥadīth literature, its sciences, books, and studies, on the assumption that they provide an ancillary function for the Qurʾānic sciences, as the ḥadīth serves to explain the Qurʾān by clarifying what is vague, providing details for what is broadly stated, and specifying what is general, as the Most Glorified states, {And We sent down to you the Reminder, such that you may clarify to the people what was revealed to them, and perchance they may reflect}, then in this case you shall witness before you an ocean with crashing waves! And if you add to this all the remains of the religious and Arabic sciences on the assumption that they all serve the Qurʾān or are derived from it, then you shall witness yourself before written works that are as mountains and encyclopedic works as plentiful as the sands, and all you will be able to say in such an instance is to verily repeat the statement of Allah, {And none knows its interpretation except Allah}.

And you would only increase in amazement if you contemplate the manner in which these authors penned their works, where they were forced to survey and absorb all the relevant aspects of the Qurʾān relating to their topics of inquiry to the extent of their human potential. Thus, an author penning a work on the difficult vocabulary of the Qurʾān would have to go through all the existing vocabulary in the Qurʾān, isolating what appears to be obscure or difficult, the one penning a work on the figurative language of the Qurʾān would have to isolate all the words in the Qurʾān consisting of figurative expressions of any kind,and similarly, whoever pens a work on the examples of the Qurʾānwould have to discuss every example that is struck by Allah in the Qurʾān, as is the case with the remaining topics. And there is no doubt that it would be impossible for any human to fully encompass the fruits of all these colossal efforts, even if he were to spend his whole life and exhaust everything at his disposal.

For this reason, the scholars gathered to create out of these sciences a new and distinct field of knowledge that may serve as a table of contents for them and a resource pointing to them, and that may become the reference point of discussion concerning them. This knowledge would become known as the ʿUlūm al-Qurʾān, in the recorded sense.

And we do not know of anyone before the fourth century AH who authored or attempted to author in the Qurʾānic sciences in the recorded sense of the term because the right impetus was not available to them to propel them to write within this genre. We know, however, that this knowledge remained gathered within the breasts of the most distinguished scholars, despite the fact that they did not record it in written books or distinguish it as a field with a name.

Indeed, the Qurʾānic sciences remained gathered in the breasts of the most distinguished scholars. Thus, we read today in the history of al-Shāfiʿī, may Allah be pleased with him, that during his tribulation in which he was accused of being the leader of the ʿAlawites in the Yemen, and he was led in chains before al-Rashīd in Baghdād as a result of this rumor, that al-Rashīd asked him, alluding to his knowledge and “How is your knowledge and favour, “How is your knowledge, O Shāfiʿī, concerning the Book of Allah, the Almighty and Majestic, for it is the most fitting of Books to begin with?” Al-Shafiʿī said, “Which among the books of Allah do you ask me of, O Commander of the Faithful? For Allah, the Most Exalted, has sent down many books” Al-Rashīd answered, “Indeed, but I have asked about the Book of Allah that has been revealed to my paternal cousin, Muhammad, may the peace and blessings of Allah be upon him.” Al-Shāfiʿī responded, “The Qurʾānic sciences are many, so do you ask me concerning the clear or ambiguous (verses), or concerning what is advanced and what is delayed, or concerning the abrogating and the abrogated, or . . . ?” And so he continued to list to him the various aspects of the Qurʾānic sciences, answering every question in a manner that amazed al-Rashīd and those in attendance.

As you can see, in this response by al-Shāfiʿī, and his silencing of those present with his truth in this tremendous incident, is a sign indicating that the hearts of the greatest scholars served as gospels to these Qurʾānic sciences before they were ever recorded in books or developed into a field. And Jalāl al-Dīn al-Balqaynī notes in the sermon of his book on al-Shāfiʿī’s speech that we have just mentioned, “The addresses of Imām al-Shāfī’s to Caliphs of BanīʿAbbās became popular, and in them is a mention of some of the Qurʾānic sciences, which we can acquire as our destination. And we do not find this to be impossible for al-Shāfiʿī, for he was one of Allah’s manifest signs in terms of his knowledge, intelligence, innovativeness, renewal, the strength of his proof, and God-given success. And he authored his book al-Ḥujja while in Iraqin order to preempt and refute the views of the schools of Ahl al-Raʾi (people of opinion), while in Egypt he authored other books in which he preempted and refuted the views of some of Ahl al-Ḥadīth (people of ḥadīth). He then authored a book for regulating the formation of legal opinions (ijtihād) and the derivation of legal rulings (istinbāṭ) as a new genre that was never established by anyone before him, for he was the first to author a work in legal theory (usūl al-fiqh), which is considered among the Qurʾānic sciences, as you may know. Ibn Khaldūn states in his Muqaddima, “The first to write about legal theory was al-Shāfiʿī, may Allah be pleased with him, and he wrote in it his famous al-Risāla in which he discussed commands and prohibitions, clear speech, traditions, abrogation, and the ruling on evidence derived from analogical reasoning . . .“

Al-Zarkashī states in his book al-Baḥr al-Muḥīṭ fī Uṣūl al-Fiqh,“Al-Shāfiʿi was the first to write on legal theory, and in it he authored in it the works al-Risāla,Aḥkām al-Qurʾān wa Ikhtilāf al-Ḥadīth wa Ibṭāl al-Istiḥsān, Jimāʿ al-ʿIlm, and Kitāb al-Qiyās, wherein he mentioned the misguidance of the Muʿtazila and his dissociation from accepting their writings . . “ May Allah be pleased with him and from the remaining mujtahid Imams.

· The First Period in Which This Conventional Term Appeared

What was known from those who authored works on the history of this field is that the period in which this usage (ʿUlūm al-Qurʾān) first appearedis the seventh century AH.

However, I was able to obtain a work from Dar al-Kutub al-Maṣriyya by ʿAlī b. Ibrāhīm b. Saʿīd, who is more commonly known as al-Ḥawfī (d. 330 AH),which is entitled al-Burhān fīʿUlūm al-Qurʾān. This work consists of thirty volumes, and what is extant of it today is 15 unedited volumes that remain in manuscript form. Thus we are able to date the development of this field some two hundred years earlier, beginning roughly in the fifth century AH as opposed to the seventh. I was very excited about reading the introduction to his work to obtain a clear idea from the author concerning the early beginnings of this field. However, this was unfortunately not possible, as the first volume remains missing, and all we have is the title of the work that appears to hint at an attempt to develop this new field. Thus, I inspected some of the available volumes and found that he lists the noble verses according to their order in the musḥaf and, he then proceeds to speak about them from the various areas of inquiry under the Qurʾānic sciences, offering a heading for each. Thus, for instance, he begins with the heading “What is said concerning His statement, the Almighty and Majestic.” He then adds the heading “What is said concerning its syntax” and proceeds to discuss its grammatical features. He then proceeds with the heading “What is said concerning its meaning and exegesis,” which he attempts to interpret by relyingon the collected traditions (manqūl) and by relying on the use of rational opinion (maʿqūl). He then moves on after their interpretation with the following heading: “What is said concerning where to stop and continue, underlying beneath it where stopping is permissible and where it is not.” He then provides separate headings for the variant readings and offers what is mentioned concerning each. He also discusses the Sharīʿā’s legal rulings related to the verses under investigation as well; thus in the verse {And observe the prayer, pay the Zakāt, and what you provide for yourselves of righteous deeds, you shall find it with Allah} of Surat al-Baqara, he discusses the times of prayer and their proofs and the niṣāb (minimal amount needed)for establishing the Zakat and its value. He also discusses the reasons for revelation (asbāb al-nuzūl) and the topic of abrogation, among other topics wherever necessary. As you can see, this work concerns the Qurʾānic sciences, but it does not organize them according to specific topics and their like, providing an exhaustive list of items meant for wider circulation, based on the wordsresembling one another that are found across the Qurʾān and their distribution throughout. It is as if this work were a work of exegesis in which the author exposes his readers to the different Qurʾānic sciences, wherever he deems it appropriate. Whatever the case, this work reflects a tremendous effort and a praiseworthy attempt in this area. May Allah abundantly reward its author for his efforts.

Then came Ibn al-Jawzī (d. 597 AH) in the sixth century AH, and he authored two important works: Funūn al-Afnān fīʿUlūm al-Qurʾān and al-Mujtabā fīʿUlūm Tataʿallaq bil Qurʾān. Each of these two remains in manuscript form at Dar al-Kutub al-Maṣriyya.

This was followed by ʿAlam al-Dīn al-Sakhāwī (d. 641 AH) in the seventh century AH who authored a work entitled Jamāl al-Qurrāʾ and by Abu Shāma (d. 665 AH) who authored a work entitled al-Murshid al-Mūjiz fī mā Yataʿallaq bil Qurʾān al-ʿAzīz, and these are,as al-Suyūṭī has pointed out, butminor examples and small fragments in comparison to the voluminous works of this kind that have been authored since then.

As for the eighth century AH, we have Badr al-Dīn al-Zarkashī (d. 794 AH) who authored al-Burhān fīʿUlūm al-Qurʾān, of which a manuscript copy exists in the Taymūrī library of Dār al-Kutub al-Maṣriyya consisting of two incomplete volumes. The ninth century AH then greeted the field with much good fortune and grace, as it continued to develop and blossom with the introduction of work by Muhammad b. Sulaymān al-Kāfījī (d. 873 AH), which al-Suyūtī praises as follows, “It is the first of its kind, and it consists of two chapters: the first mentions the meanings of exegesis (tafsīr), interpretation (taʾwīl), the Qurʾān, the Sura, and the verse (ʾaya), while the provides the necessary conditions for engaging in rational interpretation (bil raʾy) of the Qurʾān.[52] These are followed by a closing section on the etiquettes of the scholar and the student, and other than this he said in the end, and this did not quench my thirst for more, nor lead me to my destination . . .” And in this century also, Jalāl al-Dīn al-Balqīnī authored his work Mawāqiʿ min Mawāqiʿ al-Nujūm.

· The Qurʾānic Sciences in the Last Century

It appears that in our day and age there positive signs of renewed activity and writing in this field. The late teacher Shaykh Ṭāhir al-Jazāʾirī has authored a significant work entitled al-Tibyān fīʿUlūm al-Qurʾān that is nearly three hundred pages in length and that was published in 1335 AH.

The late teacher Shaykh Maḥmūd Abu Daqīqa also authored a valuable treatise for the students specializing in al-Daʿwa wal Irshād (daʿwa and guidance)in Kulliyyat Uṣūl al-Dīn, and he was followed by the teacher Shaykh Muhammad ʿAlī Salāma, who authored a rich work for the students specializing in the same degree entitled Manhaj al-Furqān fīʿUlūm al-Qurʾān. Besides this, there are many published works in the different areas of the Qurʾānic sciences by great scholars and academics, and we shall mention some of the distinguished names who are now deceased, like Shaykh Muhammad Bakhīt, Shaykh Muhammad Ḥasanayn al-ʿAdawī, and Shaykh Muhammad Khalaf al-Ḥusaynī, who authored works on the revelation of the Qurʾān in the seven styles of recitation (aḥruf) and on other topics,and the late al-Sayyid Muṣṭafa Ṣādiq al-Rifāʿī, who authored on the miraculous inimitability of the Qurʾān, which was published by the generous donation of the late King Fuʾād I. Among them also is the late Shaykh ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz Jāwīsh, who penned a series of lectures on the effects of the Qurʾān on the liberation of the human mind that he presented at Nādī Dar al-ʿUlūm, the late Shaykh ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz al-Khawlī, who authored the work al-Qurʾān al-Karīm wa Ṣifat Atharih, Ḥidāyatih, wa Iʿjāzih, and the late Shaykh Ṭanṭāwī Jawharī, who authored the treatise al-Qurʾān wal ʿUlūm al-ʿAṣriyya.

In addition to this, his excellency, the great Ustāz, Shaykh Muhammad Muṣṭafa al-Marāghī, the shaykh of al-Azhar Mosque, set out to establish the permissibility of translating the Qurʾān, and he wrote on this a masterful treatise, and he was assisted in this by others. On the other hand, the great teacher Shaykh Muṣṭafa Ṣabrī, the former Shaykh al-Islam of Turkey, responded to this in his own rigorous work, Masʾalat Tarjamat al-Qurʾān, and he was aided in this view by others.

· Conclusion

To summarize, you can gain from what has been mentioned that the Qurʾānic Sciences as a recorded field of study was launched in full vigor at the hands of al-Ḥawfī, al-Sakhāwī, and Abī Shāma over the sixth and seventh centuries AH, it then continued to develop during the eighth century under the care of al-Zarkhashī, and it blossomed during the ninth century AH under the attention of al-Kāfījī and Jalāl al-Dīn al-Balqīnī.

It then went on to bloom, bearing its fruits of every kind, by the end of the ninth century AH and the beginning of the tenth under the supervision of the unrivaled master of that period, the author of al-Taḥbīr andal-Itqān fīʿUlūm al-Qurʾān, al-Suyūṭī. After this, its development stagnated up to this last century, only to once again show signs of new signs of revival during the past few years, and perchance it shall return to its former glory. {Indeed, the victory of Allah is near}.

[1]ʿUlūm al-Qurʾān Min Khilāl Muqaddimāt al-Tafsīr, 39; Mabāḥith fī ʿUlūm al-Qurʾān, by Manāʿ al-Qattān, 15; Dirāsāt fī ʿUlūm al-Qurʾān al-Karīm, by Ustadh/Dr. Fahd al-Rūmī, 21; ʿUlūm al-Qurʾān Bayn al-Burhān wal-Itqān, 20; al-Madkhal li Dirāsat al-Qurʾān al-Karīm, by Muhammad Abī Shabhah, p. 18.